[[{“value”:”

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

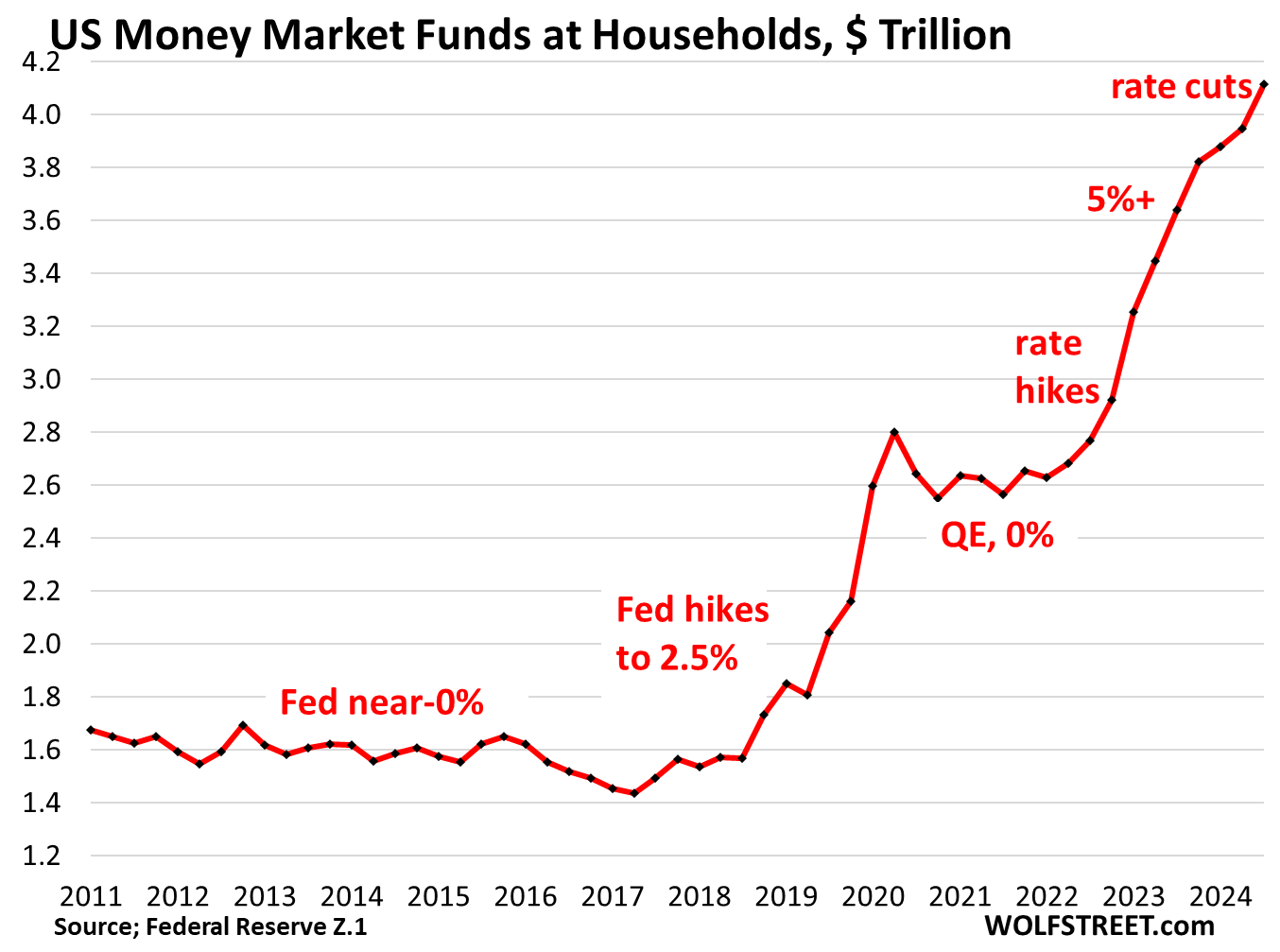

Balances in money market funds held by households at the end of Q3 jumped by $167 billion from the prior quarter to $4.11 trillion, according to the Fed’s quarterly Z1 Financial Accounts released yesterday. This massive jump in MMF balances occurred even as the Fed started its rate-cut cycle with a 50-basis point cut on September 18, and even as MMF yields have been meandering lower since July in anticipation of the cuts.

Yields of MMFs roughly parallel three-month Treasury yields but are often a little higher. Three-month Treasury yields started descending in July from about 5.36%, and by September 18, the day of the rate cut, were down to 4.76%, and by the end of September, they were down to 4.60%. But even those lower yields were still good enough, and households poured more cash into MMFs in Q3.

These MMF balances include retail MMFs that households buy directly from their broker or bank, and institutional MMFs that households hold indirectly through their employers, trustees, and fiduciaries who buy those funds on behalf of their clients, employees, or owners.

MMFs are mutual funds that invest in relatively safe short-term instruments, such as Treasury bills, high-grade commercial paper, high-grade asset-backed commercial paper, repos in the repo market, and repos with the Fed – the Fed’s “Overnight Reverse Repos” (ON RRPs).

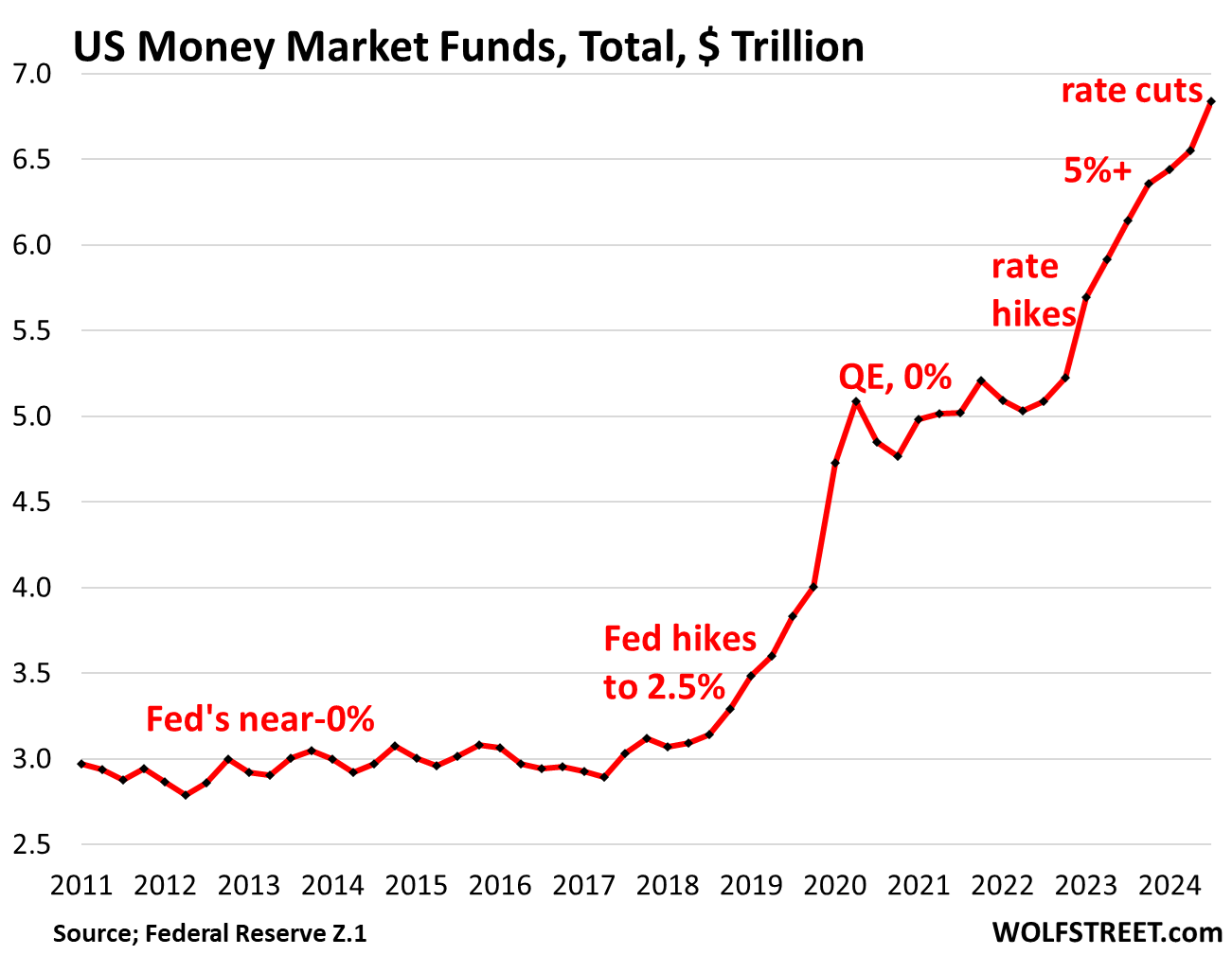

Total MMFs (held by households and institutions) jumped by $291 billion in the quarter to $6.84 trillion at the end of Q3, having ballooned by 53% since Q1 2022 when the rate hikes started from near 0%, and having more than doubled since 2018, when the prior rate-hike cycle took the Fed’s policy rates to 2.25%.

But even after the Fed started cutting rates in 2019 and slashed rates to near 0% in Q1 2020, cash continued to pour into MMFs. It wasn’t until Q3 2020, that relatively small amounts of cash left MMFs, and then balances remained essentially stable. When yields started rising again in 2022, a tsunami of cash washed over the funds. And that has continued so far despite lower yields:

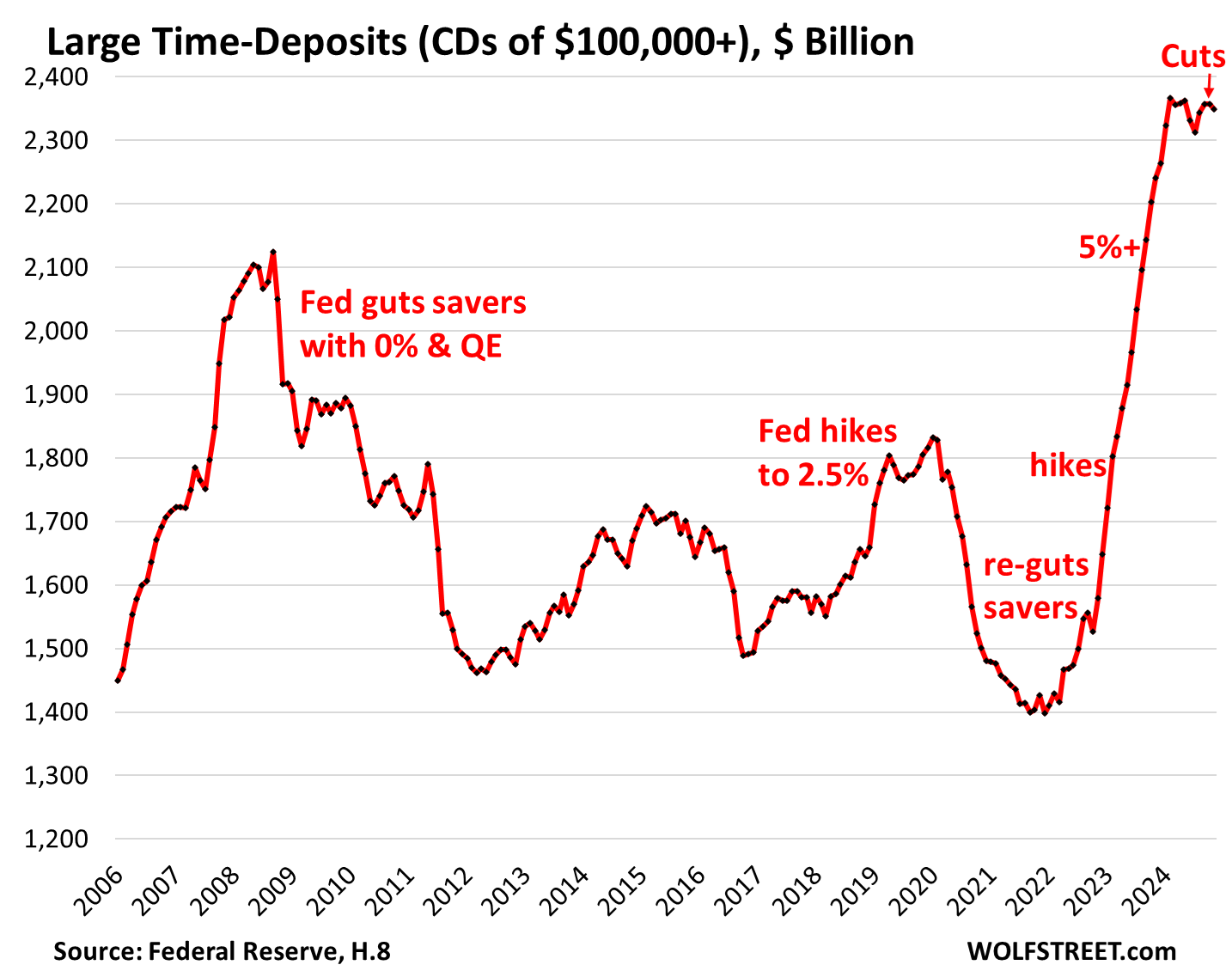

When MMF yields began to move higher in 2022, banks had to respond by offering higher yields on CDs and savings accounts in order to motivate new customers to put their cash into the bank and to motivate existing customers to not yank their cash out. But paying higher interest rates on deposits increases banks’ cost of funding, and they don’t do it unless they have to in order to hang on to their customers’ cash (deposits).

Deposits – loans from customers to banks that form the primary funding of banks – are generally “sticky,” especially in checking accounts and low-yield savings accounts that customers are too lazy to empty out. This stickiness of deposits means that even when rates rise, a big portion of deposits doesn’t get the higher rates but stays at those banks nevertheless, and customers pay the “loyalty tax” to the bank. Banks count on it. Some deposits did leave when yields rose, and banks had to deal with it by selectively offering higher interest rates.

But by early 2024, banks had enough deposits and started dialing back the interest rates they offered even as MMF yields were still over 5%. And cash stopped pouring into CDs.

Large Time-Deposits (CDs of $100,000 or more) peaked in February at $2.37 trillion and then sort-of flatlined with a dip in June and July followed by a partial bounce-back in August and September. Then balances eased again, to $2.35 trillion at the end of November, according to the Fed’s monthly H.8 banking data released today.

In the two years since March 2022 (when the rate hikes began) and February 2024, large time-deposits surged by $951 billion, or by 67%. And when banks started dialing back their rates, the surge stopped, but the balances have remained sticky so far at these levels:

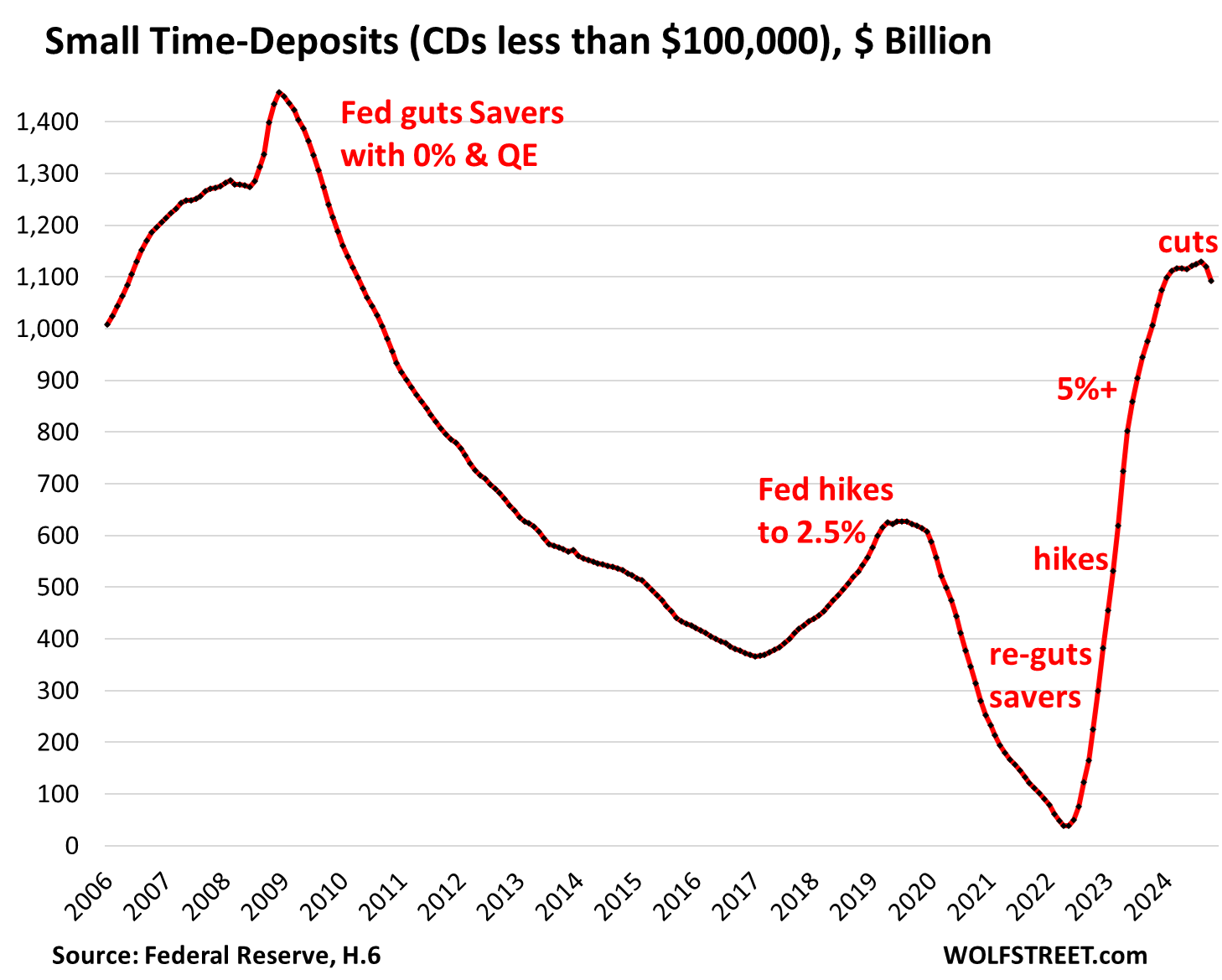

Small Time-Deposits (CDs of less than $100,000) dropped to $1.09 trillion in October following the first rate cut, according to the Fed’s latest Money Stock Measures. The data for November has not yet been released.

These small CDs reflect what regular folks are doing with their savings. When the Fed gutted their cash flow from savings in 2008, they lost interest in CDs and the cash reverted to savings and checking accounts, or went somewhere else.

From the end of 2008 through mid-2022, these CD balances had plunged by 97%, despite the rate-hike hump in 2018. When rates rose in 2022 and 2023, balances exploded. These small CDs are very sensitive to interest rates; they’re not “sticky” at all. They come and go.

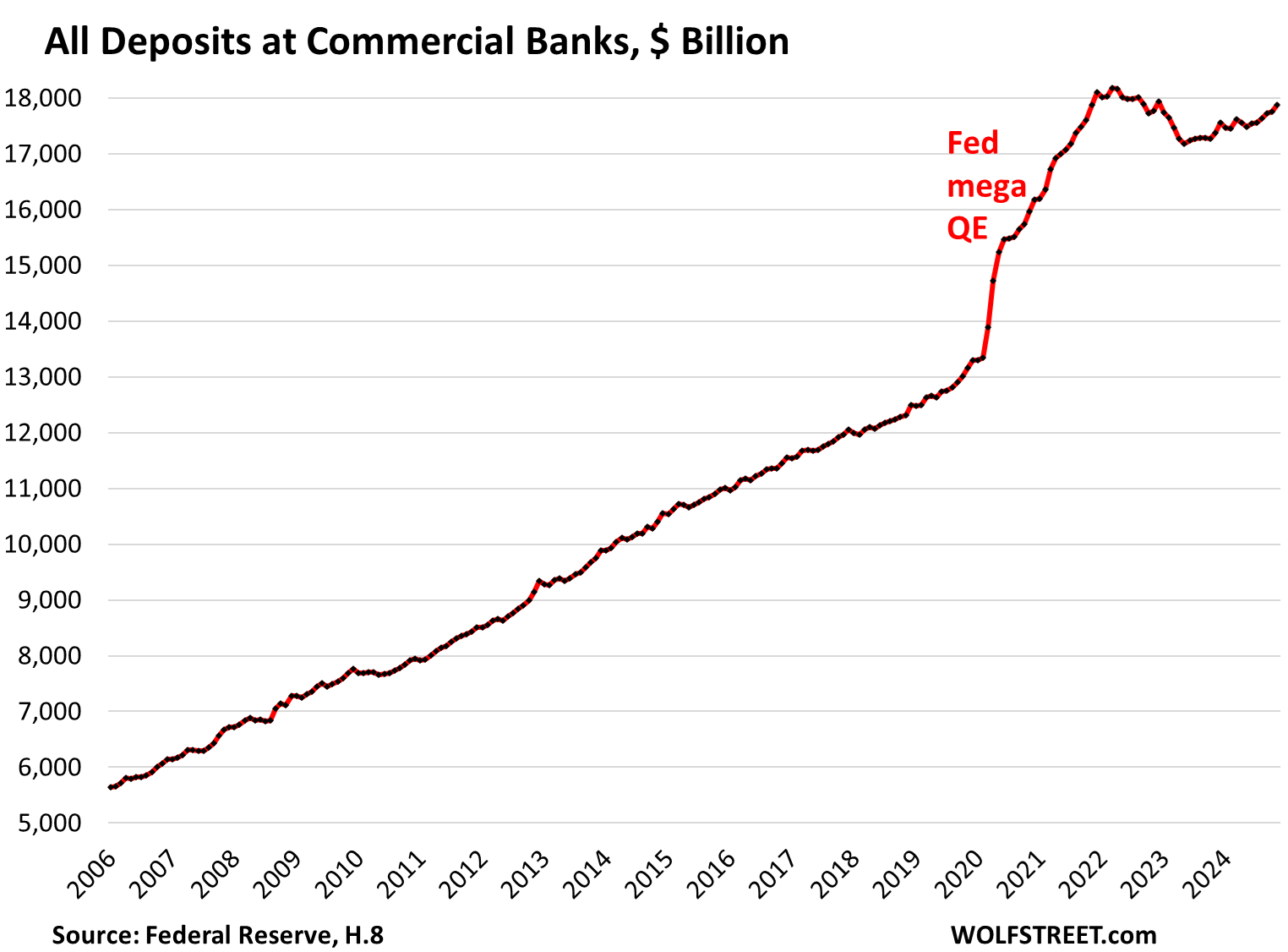

Total deposits at all commercial banks edged up to $17.9 trillion in November, according to the Fed’s banking data released today. These are deposits by all bank customers: households, businesses, and state and local government entities. But the Federal Government’s checking account is no longer with commercial banks and is not included here; during the Financial Crisis, it was moved to the New York Fed.

All commercial banks combined lost about $1 trillion in deposits between the initial rate hike in March 2022 through May 2023, just ahead of the last rate hike. This kind of plunge in deposits, in dollar terms and in percentage terms, had never before occurred in the data going back to 1975.

Three banks collapsed during that time – Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic – and another was forced to shut down by regulators – Silvergate Capital – because depositors tried to yank their cash out all at the same time. But starting in June 2023, deposits started slowly rising again and have by now regained a large portion of the plunge:

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

The post Money Market Funds, Large CDs, Small CDs, and Total Deposits: Americans’ Huge Piles of Interest-Earning Cash as Rates Drop appeared first on Energy News Beat.

“}]]