[[{“value”:”

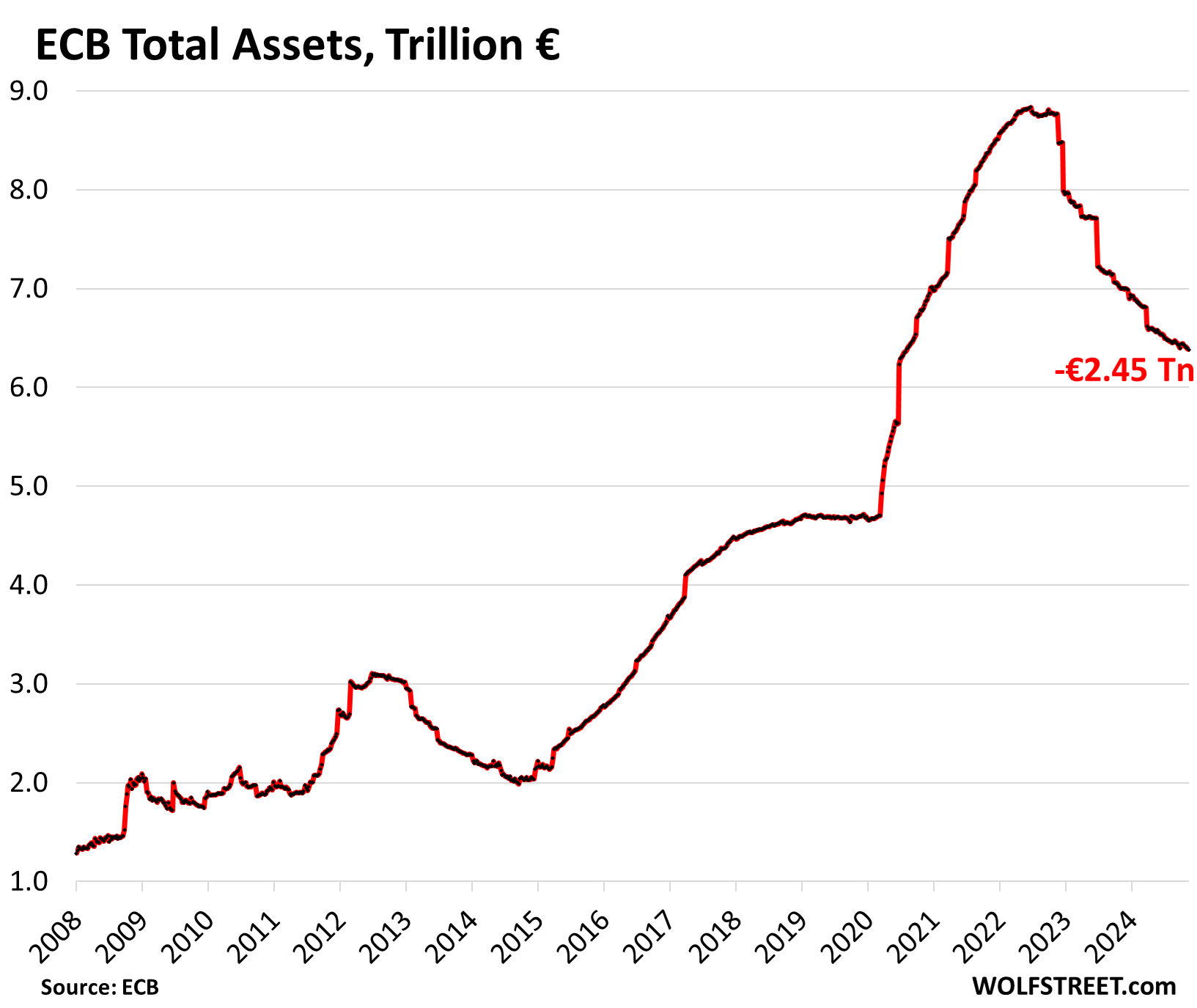

Meanwhile, the ECB’s QT marches on, balance sheet has shed €2.45 trillion since the peak, or 59% of its pandemic QE.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

The ECB’s own measure of wage increases, its index of “Negotiated Wages,” is based on collective bargaining agreements after they were negotiated between employers and organizations that represent workers. It’s a forward-looking measure, reflecting wage increases that are going to be implemented soon. “Negotiated wages” cover about two-thirds of the Euro Area economy. These “negotiated wages” exclude bonuses, overtime, and other individual compensation that is not linked to collective bargaining.

And it blew a fuse today. In Q3, “negotiated wages” spiked by 5.4% year-over-year, according to the ECB today, after the false-hope deceleration in Q2.

In its June economic bulletin, the ECB explained: “Monitoring wages is a key element in the ECB’s approach to analysing the inflation outlook. This reflects the prominent role of wages in the dynamics of underlying inflation, in particular in the services component, which has remained persistent.”

It also said that the “outlook for further disinflation” was predicated “on the expectation of moderating wage growth.” Q2 brought the moderating wage growth, triggering the ECB’s initial rate cuts. Q3 blew all of this out of the water.

Big wage increases are obviously great for households, and a great way to stimulate demand, as households have more spending money, and they feel better, and so they spend more, creating more demand and more jobs, and more economic growth, and that’s great.

The ECB’s concern is that big wage increases also add to the fuel that keeps inflation going, particularly in services where wages are a big cost input that companies try to pass on via price increases that translate into higher inflation rates.

And services inflation has remained stubbornly hot in the Euro Area, despite the massive plunge in energy prices, and declines in prices of many goods. The services CPI accelerated to 4.0% year-over-year in October, after a deceleration in September, according to Eurostat earlier this month. It has been stubbornly rising at about 4.0% year-over-year since November 2023 (red in the chart below).

Services inflation of 4.0% is far too high to get to the ECB’s 2% inflation target, once the drop in energy prices ends, and goods prices return to normal patterns.

The services CPI started surging in 2022 to reach 5.6% in mid-2023. It then decelerated through November 2023 to 4.0%, and has gotten stuck there – more than double the year-over-year increases in the 10 years before then.

Core CPI, which excludes food, energy, tobacco, and alcohol, has been rising by roughly 2.7% year-over-year since April (blue).

This jump in negotiated wages will translate into hefty actual wage increases when they’re implemented over the coming months and next year, which will then feed further into the stubborn services inflation. The ECB governors are going to have their hands full trying to agree on how little and how slow to cut to not make inflation worse. But rate cuts are not permanent. If inflation re-heats further, the ECB can always nudge its policy rates back up.

Meanwhile, the ECB has been making progress with QT. Total assets dropped to €6.38 trillion, down by €2.45 trillion from the peak, according to its balance sheet released yesterday. It has unwound 59% of its pandemic-era QE so far:

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()

The post ECB’s Own Measure of Wage Increases Blows Fuse, Sets Off Alarms about Stubbornly Hot Services Inflation appeared first on Energy News Beat.

“}]]